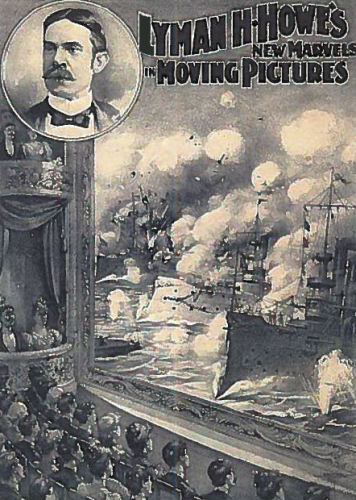

Early filmmakers faced a dilemma: how to capture the drama of war without getting themselves killed in the process. Their solution: fake the footage

The lesson here, surely, is not that the camera can, and often does, lie, but that it has lied ever since it was invented. “Reconstruction” of battle scenes was born with battlefield photography. Matthew Brady did it during the Civil War. And, even earlier, in 1858, during the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny, or rebellion, or war of independence, the pioneer photographer Felice Beato created dramatized reconstructions, and notoriously scattered the skeletal remains of Indians in the foreground of his photograph of the Sikander Bagh in order to enhance the image.

Most interesting of all, perhaps, is the question is how readily those who viewed such pictures accepted them. For the most part, historians have been very ready to assume that the audiences for “faked” photographs and reconstructed movies were notably naive and accepting. A classic instance, still debated, is the reception of the Lumiere Brothers’ pioneering film short Arrival of the Train at the Station, which showed a railway engine pulling into a French terminus, shot by a camera placed on the platform directly in front of it. In the popular retelling of this story, early cinema audiences were so panicked by the fast-approaching train that—unable to distinguish between image and reality—they imagined it would at any second burst through the screen and crash into the cinema. Recent research has, however, more or less comprehensively debunked this story (it has even been suggested that the reception accorded to the original 1896 short has been conflated with panic caused by viewing, in the 1930s, of early 3D movie images)—though, given the lack of sources, it remains highly doubtful precisely what the real reception of the Brothers’ movie was.

Read More: The Early History of Faking War on Film via a really good and informative post from aamorris.net: NASA & The Military Industrial Complex Presents: 3D Special Effects For Entertainment

No comments:

Post a Comment