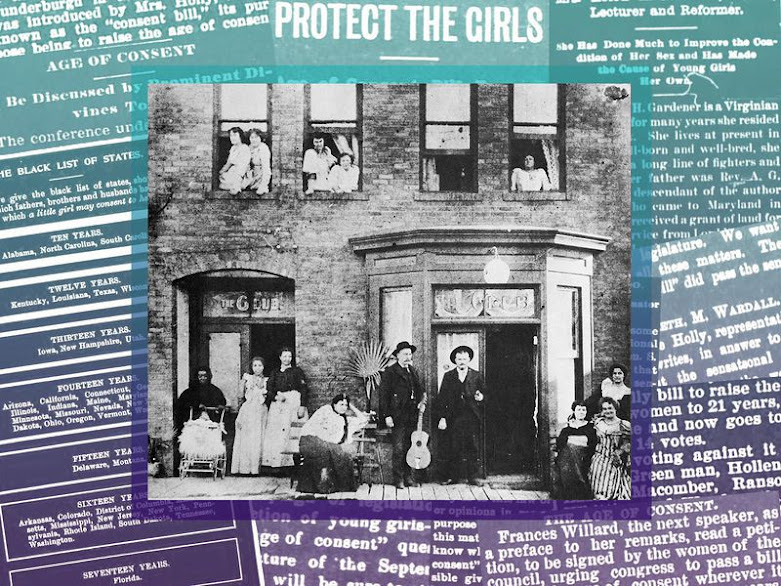

The very first bill ever proposed by a female lawmaker in the United States came from Colorado state representative Carrie Clyde Holly in January 1895. Building on a decade of women’s activism, Holly’s ambitious legislation sought to raise the age of consent in the state to 21 years old. In 1890, the age at which girls could consent to sex was 12 or younger in 38 states. In Delaware, it was seven. Such statutes had consequences extending from the safety and wellbeing of young girls to women’s future place in society and their potential for upward mobility. To women reformers of various stripes—temperance advocates, labor leaders and suffragists—Holly and her historic bill symbolized what was possible when women gained a voice in politics: the right to one’s own body.

By petitioning legislators in dozens of states to revise statutory rape laws, these women forged interracial and cross-class collaborations and learned the political skills they’d later use to push for suffrage. Today, as the United States marks the centennial of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the impact of women in politics, and their fight to maintain their bodily autonomy, remain touchstones of the nation’s political conversation.In the late 19th century, the prevalence of sexual assault and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) compelled thousands of women to political action. Based on English Common Law dating back to the 1500s, American lawmakers had selected 10 or 12 as the age of consent to coincide with the onset of puberty, as if once a girl menstruated she was ready to have sex. Men accused of raping girls as young as 7 could (and did) simply say “she consented” to avoid prosecution. Reformers understood that once “ruined,” these young victims of assault could be forced into prostitution because no man would marry or hire a “fallen woman.”

Prostitution especially concerned wives and mothers because, before penicillin became widely available in 1945, syphilis and gonorrhea were more widespread than all other infectious diseases combined. Wives who unknowingly contracted STIs from their husbands could pass them on to their unborn children, resulting in miscarriages, fetal abnormalities, blindness, epilepsy and unsightly “syphilis teeth.” In most cases, women could not successfully sue for divorce, support themselves, or retain custody of their children if they did divorce. What they wanted was a way to hold men accountable for their actions and a semblance of control over what happened to their bodies and their children. Women believed that raising the age of consent for girls would diminish the number of working prostitutes and alleviate a host of social ills caused by the sexual double standard. They were partially right.

Most often, women worried about sexual violence, prostitution, and STIs joined the temperance movement because they believed that alcohol fueled abuse against women and children and because, unlike discussing sex, talking about alcohol didn’t breach societal taboos. In 1879, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was by far the largest women’s organization in the country. Over the next ten years, membership quadrupled and the WCTU counted chapters in nearly every community in the country. But despite their growing organizational strength, temperance advocates hadn’t yet achieved their goals of major legislative change. In addition to working to ban alcohol and bring the “moral force” of women to the public sphere, temperance groups led the crusade to raise the age sexual consent for girls.

This American movement drew inspiration from its counterpart in England. British purity reformers had succeeded in raising the age of consent to 13 in 1861, and the movement received international attention in 1885 after muckraking journalist William T. Stead went undercover in London’s brothels. Stead published a series of salacious articles, collectively titled “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon,” in the Pall Mall Gazette detailing how London’s husbands and fathers paid top dollar to deflower child virgins in the city’s brothels. Within months, public outcry led Parliament to raise the age of consent to 16.But change in the United States proved much more challenging. Following the success of the British campaign, the WCTU made raising the age of consent a top priority because, as the group’s long-term president Frances Willard remarked, “the Siamese twins of vice are strong drink and the degradation of women.” Confident that they were following in the path of Christ, these otherwise traditional, middle-class women were emboldened to discuss sex, albeit in veiled terms. Willard did not generally use words like “sex,” “rape,” or “syphilis” in front of male lawmakers or even in front of her female membership. Rather, she explained that “a wife must be the unquestioned arbiter of her own destiny” and the WCTU referred their efforts to curb sexual violence as “the promotion of purity.”

Between 1886 and 1900, the WCTU petitioned every state legislature in the country, garnering more than 50,000 signatures in Texas alone, and dispatched women to legislative sessions from coast to coast to demand that the age of consent be raised to 18. Many lawmakers rejected women’s presence in public affairs and further resented the unprecedented campaign to curtail white men’s sexual prerogatives. So they stone-walled WCTU members, inserted neutralizing or mocking language in their proposed bills, and occasionally outright banned women from their galleries. The few legislators who went on record in support of young ages of consent voiced sympathy for hypothetical men who would be ensnared into marriage by conniving girls who consented to sex and later threatened to press charges. Nevertheless, by 1890, the WCTU and their allies in the labor and populist movements had succeeded in raising the age of consent to 14 or 16 in several states. This marked significant progress, but women advocates still wanted to raise it to 18.

Reformers lamented the challenges of directing public attention to this ongoing outrage, especially when respectable women were not supposed to talk about sex. In 1895, Willard forged an unlikely alliance with the “freethinking” (atheist or agnostic) feminist Helen Hamilton Gardener, who made raising the age of consent her focus in the 1890s. Though hardly anyone—least of all Willard—knew it, Gardener herself was a “fallen woman” who had moved and changed her name when she was 23 after Ohio newspapers publicized her affair with a married man. Feeling constrained by nonfiction and the Comstock Laws (which prohibited the publication or transmission of any “obscene” material), Gardener turned to fiction to dramatize the dire consequences of sexual assault and spur a complacent public to action. After the publication of her two novels, Is This Your Son, My Lord? (1890) and Pray You Sir, Whose Daughter? (1892), Gardener became known as “The Harriet Beecher Stowe of Fallen Women.”

What Raising the Age of Sexual Consent Taught Women About the Vote | Smithsonian Magazine

The age of consent was clearly designed for population control before birth control was possible to do the job. This idea that women shouldn't have sex until they are 18 is nonsense. I'm not promoting pedophilia or intergenerational sex but women are able to reproduce at 13. That's how they're created. To start being mothers at 13.

If you read books on primitive tribes studied 75-100 years ago, they didn't wait until the woman is 18 to allow sex. It's laughable. There is no time to waste repopulating the tribe by saying the woman isn't ready until 18. As soon as the woman is ready to reproduce they started having sex to do so. This consent shit is a fictional construct created to make sure men and women don't get together until they're almost in their 20s. Putting off the possibility of motherhood.

It controls people to stay in a mindset to have kids in your thirties or later. Keep putting it off even though most women are ready to go at 13. This article highlights these agenda driven movements started to set up a Hegelian Dialect of why the age of consent should be raised. The story of how since there was an alleged plague of women getting raped, STDs, etc. Put the fear out there so people accept we must make sure women can't have sex early and reproduce. Of course the more effective birth control pills, condoms and other birth control measures came along 70 years later so consent took a back seat to the pharmaceutical industry with controlling the population. Still the Smithsonian tries to tie the American Women's right to vote (1920) to the age of consent movement. Like women were being held back with no proper age of consent and also like voting or government matters anyways. It's all bullshit. Just cons on top of cons.

No comments:

Post a Comment